50

Years

As Native Forward Scholars Fund celebrates 50+ years, it is important to look back at the history of the organization and the people whose foresight and vision led to the creation of Native Forward Scholars Fund.

Early Origins

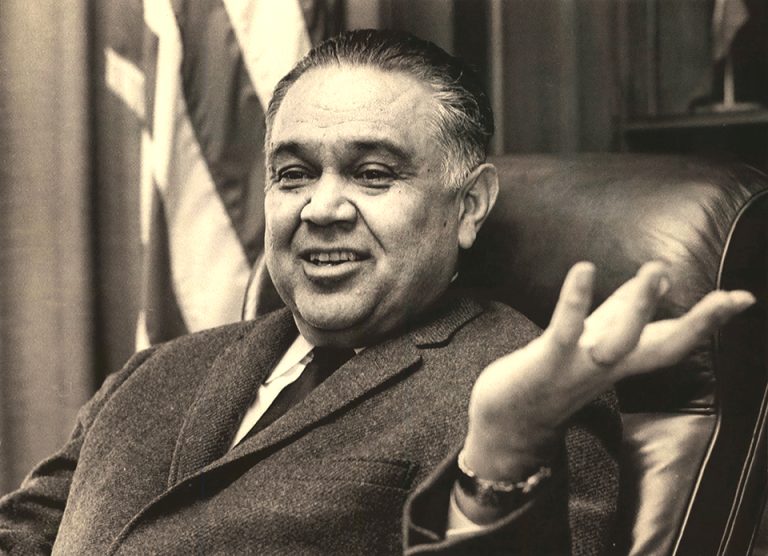

One of the co-founders of what today is known as Native Forward Scholars Fund was Robert L. Bennett (Oneida). Charles “Chuck” Trimble, one of the first Board Members, remembered Bennett as, “a very deep gentlemen and a gentle soul. I saw him always looking for opportunities for Indian people.” His role as a co-founder is one of the many times Bennett saw an opportunity for Indian people, which ultimately created opportunities for thousands of Native students over the last 50 years.

Bennett was born on the Oneida Indian Reservation near Green Bay, Wisconsin, in 1912. He attended Haskell Institute in Kansas before he studied law at Southwestern University Law School in Washington, D.C., where he earned his law degree in 1941. Much of his legal work supported Native land claims. For this work, he was awarded the Indian Achievement Award in 1962 and the Outstanding American Indian Citizen Award in 1966. His commitment and work representing American Indians caught the attention of many, including President Lyndon B. Johnson.

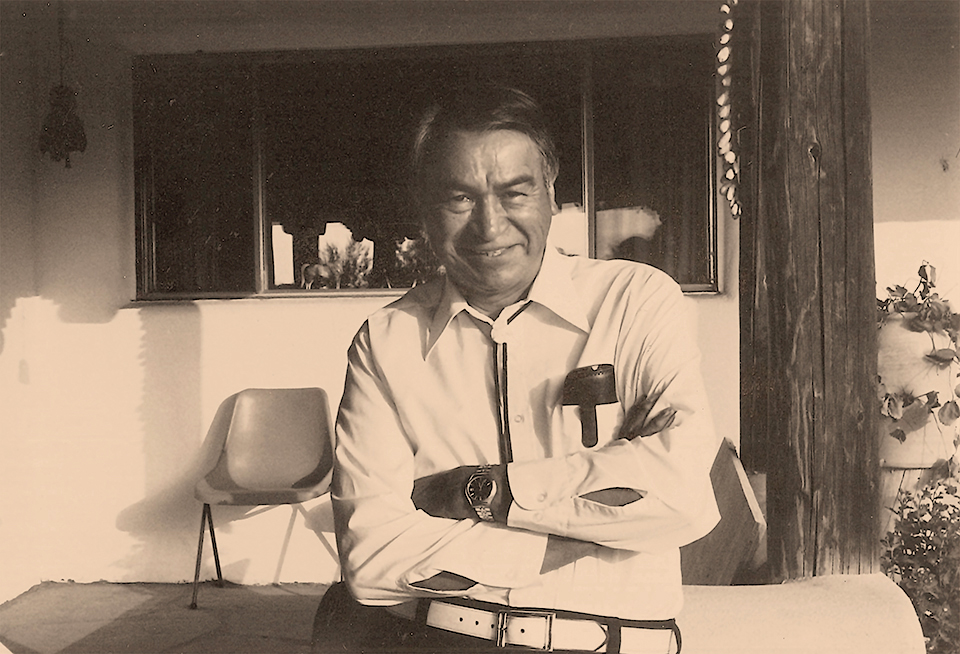

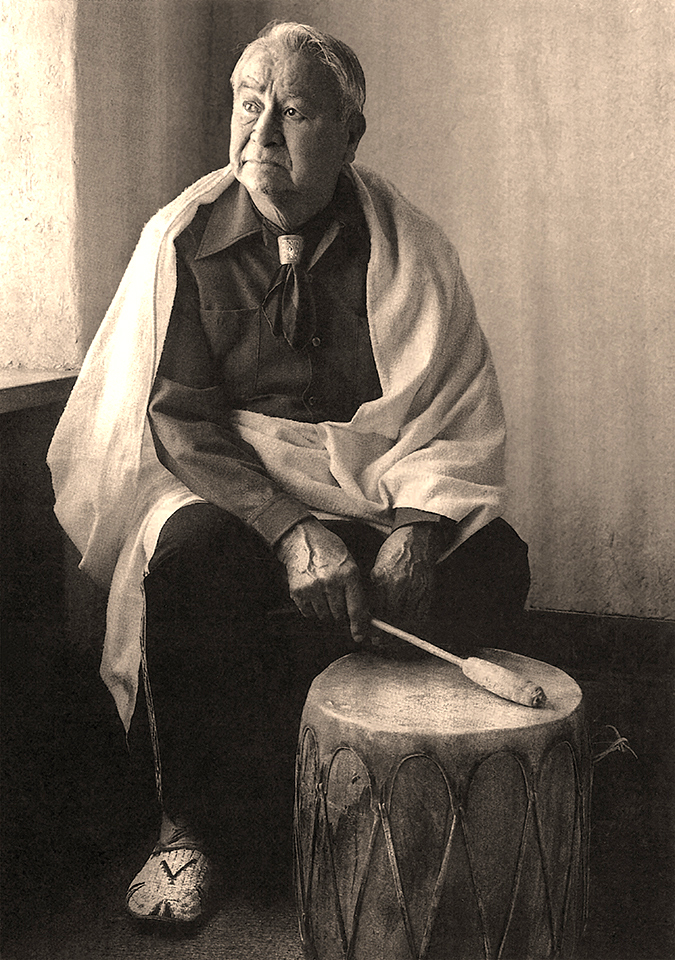

In 1966, Bennett was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to serve as the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. This appointment was historic as Bennet was only the second Native American to serve in this role. In this capacity, he often visited area offices where he was disappointed to find none were headed by Native Americans. The seeds of this observation had likely been sown earlier at meetings with John C. Rainer (Taos Pueblo). Rainer and Bennett met often during their time in Washington, D.C., and could not help but notice the lack of American Indian/Alaska Native professionals in all fields. They knew that much of this was due to a lack of funding for students seeking graduate degrees. In fact, in 1967, a report on Indian Education for the American Indian Policy Review Commission noted there were only 13 Native students enrolled in graduate studies. This further proved the need for more funding and opportunities to fund Native students in graduate studies.

In 1967, only 13 Native students were enrolled in graduate programs.

Scholarship Fund for Native Graduate Students Established

In 1969, Bennett left the Bureau of Indian Affairs and moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where he became the director of the American Indian Law Center. That same year, Rainer was selected to direct the New Mexico Commission of Indian Affairs. As their paths crossed again in New Mexico, they set out to find a solution to the issues they had identified during their time in Washington, D.C. One of the solutions was to create a scholarship program focused on funding Native students in graduate and professional programs.

To this end, the newly established National Indian Scholarship Program was founded at the University of New Mexico in August of 1969. One of the first steps was establishing a board to help set priorities and help get the word out about the new program. The first Board of Directors comprised some of the most well-known Native scholars and professionals.

Trimble remarked it was “a virtual Who’s Who of Indian scholars and leaders. They were all doers.” The Board included Joe Sando (Jemez Pueblo), Dave Warren (Santa Clara Pueblo), Lucy Covington (Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation), Ada Deer (Menominee), Overton James (Chickasaw), Leah Manning (Shoshone-Paiute), Chuck Trimble (Oglala Sioux Tribe), Rainer and Bennett.

The members voted to set up an independent office, apply for tax-exempt status, and named Bennett the General Director. On November 14, 1970, Rainer announced a $15,000 transfer from the Donner Foundation to provide direct scholarship assistance. This grant led to developing a contract with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The following year Bennett, Warren, and Sando signed the Articles of Incorporation, and the name of the program was changed to American Indian Scholarship, Inc. That year, one of the first scholarships awarded was to Donald A. McCabe, who awarded $1,200 to support his studies in business administration. McCabe would go on to serve as President of the Southwest Indian Polytechnic Institution and would be one of the first of thousands of success stories and alumni.

The work of the Center became even more critical in 1981 when the Reagan Administration reduced funding for all levels of Native higher education from $282 million to $169 million. Around this time, the program also received the results of a survey they had sent to past recipients to evaluate its effectiveness and provide information for future proposals. They found they provided financial assistance to less than one-fifth of all Native students attending graduate school, and half of the recipients were women. The reduction in federal funding and survey results highlighted the need to support their work. The National Indian Lutheran Board donated $10,000 as seed money to generate more funds. Exxon, Texaco, Arco, and Syntex also contributed.

By 1988, the American Indian Graduate Center was well established. That year, 152 women and 140 men received funding. These students represented 81 Tribes from 22 states. The students studied law, health, religious studies, natural resources, and fine art.

American Indian Graduate Center

Another milestone was reached in 1989 as the organization celebrated its 20th anniversary. The program underwent another name change to become the American Indian Graduate Center. The name was changed to reflect the organization’s expansion to become a national center with expanded services and activities. As the American Indian Graduate Center entered the 1990s, it expanded its work and footprint with a $65,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Energy for a tracking project to develop a national database of all Native college students to be used as a way to identify potential graduate students for internship and employment opportunities. The database would also assist in identifying and documenting the needs of Native students.

Five years later, the American Indian Graduate Center surveyed all federally recognized Tribes to identify their future employment needs. The top ten professions reported (in order of need) were business manager, lawyer, accountant, natural resource manager, doctor, teacher, counselor, financial analyst, engineer, and computer technician. The survey also found less than 3% of Tribal members had a college degree. American Indian Graduate Center used this data to inform its work and as reminders of the importance of its mission.

Gates Millennium Scholarship Program

The Center continued to grow and reached another major milestone in 2001. American Indian Graduate Center was selected as one of the four partner organizations to help administer the Gates Millennium Scholarship Program. This selection required the American Indian Graduate Center to create American Indian Graduate Center Scholars, Inc. to manage the scholarship. This addition doubled the staff and office space needed to administer the Gates Millennium Scholarship. A generous grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded the scholarship. The goal of the Gates Millennium Scholarship Program was to support 20,000 outstanding, low-income American Indian/Alaska Native, African American, Asian Pacific Islander American, and Hispanic students with the opportunity to complete their undergraduate studies in the degree of their choice.

The early 2000s were marked by tremendous growth, but the American Indian Graduate Center also saw huge losses. Rainer passed away on September 22, 2001, with Bennett passing away that next year. Fortunately, they witnessed over 30 years of growth from the scholarship program they started in 1969.

Native Forward Scholars Fund

In 2022, the organization’s name was changed to Native Forward Scholars Fund. Today, it continues to build and add partners to its work. Through the support of endowed gifts, federal resources, corporate support, foundations, alumni, and individual private donations, Native Forward Scholars Fund continues to grow. Last fiscal year, Native Forward Scholars Fund awarded about $11 million in scholarships and academic support services to 1,343 Native scholars. These scholars represent 193 Tribes from 48 states. The impact of Native Forward Scholars Fund can be seen throughout Indian Country.

As Chuck Trimble looked back on the organization’s history, he remarked on the vision of Bennett, “A lot of times things like this turned into a one-time offering. Instead, they built an organization with the capacity to grow and acquire more funding to provide more opportunities. I really think Bennett had a lot to do with that.” It’s hard not to hear the smile in Trimble’s voice as he recalls the beginnings of Native Forward Scholars Fund.

What started as the idea of two men has grown to become the premier national resource in funding and continues to empower the next generation of Native scholars across all sectors. It is hard to find a Native professional who doesn’t have a connection to the Native Forward as an alumnus or friend of the organization. Those who receive support from Native Forward often have similar feedback and recognize the organization is not just a scholarship-granting organization; it is family.

The dream of Bennett and Rainer is being realized by so many. Bennett would be happy to know that if he were to walk into a BIA field office today, he would be met by another Native person running the office, surrounded by Native staff. His dream of creating Native professionals extends past regional bureau offices to doctor’s offices, classrooms, courts, laboratories, agencies, Tribal offices, and beyond.

OUR EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS

John Rainer (Taos Pueblo), 1969–1982

Lorraine Edmo (Shoshone-Bannock), 1984–1992

Oran LaPointe (Rosebud Sioux), 1992–1994

Reginald Rodriguez (Laguna Pueblo), 1994–1996

Hilton G. Queton (Kiowa-Seminole), 1997–1999

Norbert S. Hill, Jr. (Oneida), 2000–2006

Philip S. Deloria (Standing Rock Sioux Tribe), 2007–2013

Angelique Albert (Confederated Salish & Kootenai), 2017–Present

OUR FOUNDING BOARD MEMBERS

Ada Deer ( Menominee)

Charles Trimble (Oglala Sioux)

David Warren (Santa Clara Pueblo/Chippewa)

Joe Sando (Jemez Pueblo)

Leah Manning (Shoshone- Paiute)

Lucy Covington (Colville )

Overton James (Chickasaw)

OUR BOARD PRESIDENT HISTORY

Ada Pecos (Jemez Pueblo)

David Mahooty (Zuni Pueblo)

Elizabeth Rodke Washburn (Chickasaw)

Grayson B. Noley (Choctaw)

Holly Cook Macarro (Red Lake Band of Ojibwe)

James M. Cox (Comanche)

Jeanne Whiteing (Blackfeet/Cahuilla)

Joseph Martin (Navajo)

Joy Sundberg (Yurok)

Louis Baca (Santa Clara Pueblo)

Lucy Covington (Colville)

Maxine Lewis-Raymond (Yurok)

Michael E. Bird (Santa Domingo Pueblo/Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo)

Osley Saunooke (Cherokee)

Rhonda Whiting (Confederated Salish & Kootenai)

Rick St. Germaine (Lac Courte Oreilles/Ojibwa)

Rose Graham (Navajo)

OUR BOARD MEMBERS, 1971-PRESENT

Alice Bathke (Navajo)

Amber Garrison (Choctaw)

Aurene M. Martin (Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa)

Beverly Singer (Tewa/Diné)

Bill Anoatubby (Chickasaw)

Cecilia Gutierrez

Chris McNeil (Alaska Native)

Dana Arviso (Navajo)

Danna K. Jackson Esq. (Confederated Tribes of Salish and Kootenai)

Darlena L. Watt (Colville)

David Lester (Creek)

David Powless (Oneida)

Dee Ann DeRoin (Ioway Tribe of Kansas)

Elizabeth Rodke Washburn (Chickasaw)

Ernest Stevens (Oneida Nation of Wisconsin)

Ernie Stevens, Jr. (Oneida Nation of Wisconsin)

Floyd Correa (Laguna Pueblo)

Franklin “Hud” Lois Oberly Jr. (Comanche/Osage/Caddo)

Georgianna Tiger (Blackfeet)

Grayson B. Noley (Choctaw)

James G. Sappier (Penobscot)

Joann Sebastian Morris (Cayuga/ Sault Ste. Marie Ojibwe)

Joel Frank (Seminole Tribe of Florida)

John Stevens (Passamaquoddy)

Kathryn W. Shanley Nakota (Assiniboine)

Kimberly Kay Teehee (Cherokee Nation)

LaDonna Harris (Comanche)

Lillian Sparks Robinson (Rosebud Sioux)

Lionel Bordeaux (Rosebud Sioux)

Lorraine Edmo (Shoshone-Bannock)

Lucille A. Echohawk (Pawnee)

Marlene Naranjo (Santa Clara/Navajo/Potawatomie)

Martha Yallup (Yakima)

Martin Seneca (Seneca)

Marvin Franklin (Iowa Tribe)

Melanie P. Fritzsche (Laguna Pueblo)

Overton James (Chickasaw)

Peterson Zah (Navajo)

Rhonda Lankford (Confederated Tribes of Salish and Kootenai)

Richard Williams (Oglala Lakota/Northern Cheyenne)

Robert Stearns (Aleut)

Rose Graham (Navajo)

Rose Robinson (Hopi)

Shenan R. Atcitty (Diné)

Stacy L. Leeds (Cherokee)

Steve Stallings (Rincon Band of Luiseño Indians)

Walter Lamar (Blackfeet Nation of Montana)

William A. Gollnick (Oneida)